Direct air capture explained

In a rapidly warming world, it is no longer enough just to cut carbon emissions. Authorities now believe the only way to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 is to take carbon out of the atmosphere. The International Energy Agency (IEA), for example, estimates we will need to have removed 7.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere within 30 years to stay on track with climate targets. The exact amount needed will depend on how fast carbon emissions can be reduced, and therefore which residual level of emissions need to be removed from the atmosphere to reach net zero.

In any event much of this will come from carbon capture and storage linked to carbon-emitting power and industrial plants. But a fair amount will have to be sucked out of the atmosphere. Perhaps the simplest and most cost-effective way to do this is through reforestation, but the time required for new trees to grow means relying on nature is an increasingly risky way of meeting 2050 targets.

Another option is direct air capture (DAC): a technology that captures and sequesters atmospheric carbon dioxide so it can be stored safely or reused.

The Technology

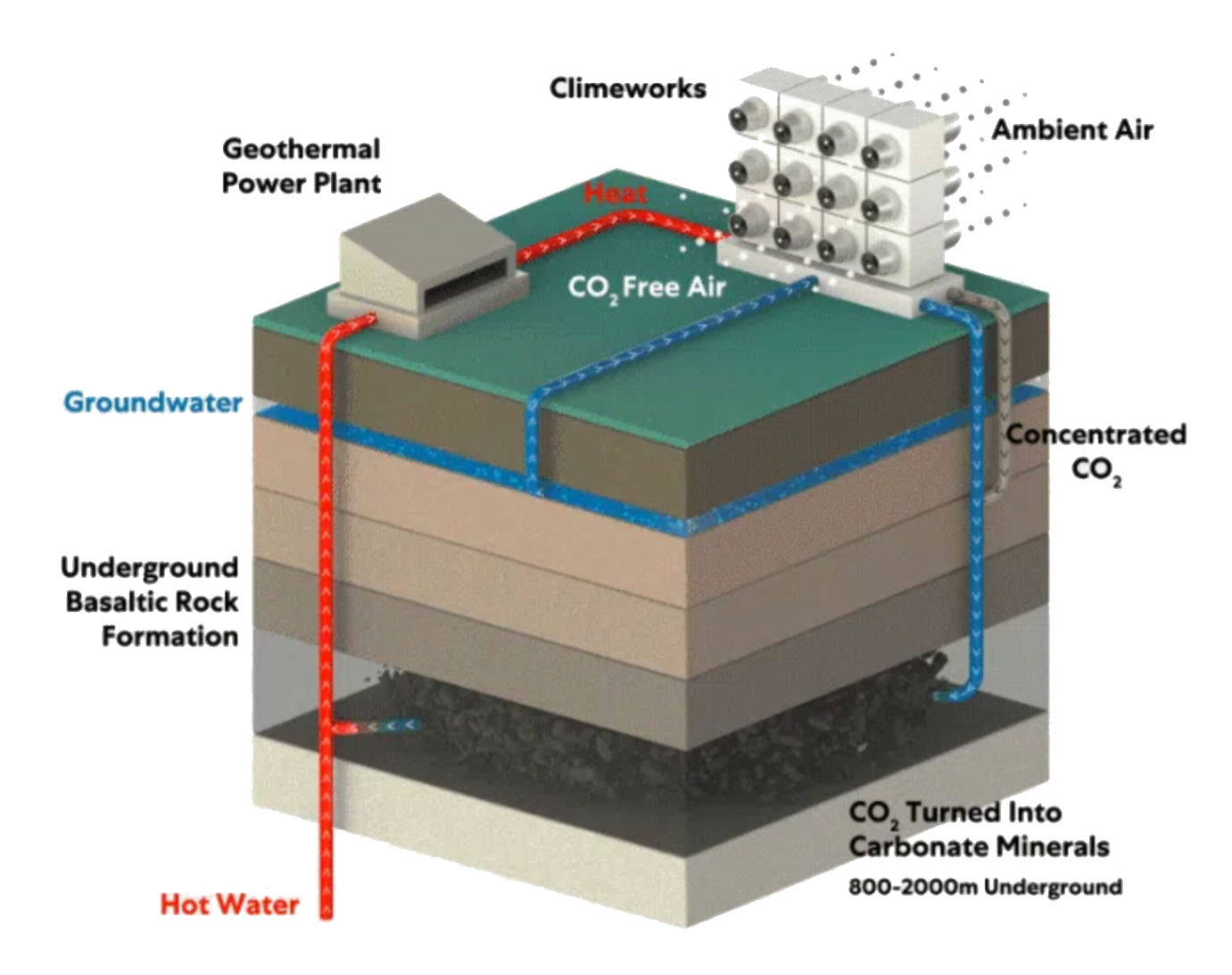

The principle behind DAC is relatively straightforward: you find a chemical that binds with carbon dioxide and then pass air over it or through it. Sodium hydroxide (caustic soda) is one chemical that does the job, turning into sodium carbonate (washing soda) in the process. In practice, DAC technologies use either liquid solvents or solid sorbents to capture carbon dioxide. The catch comes when you need to get the carbon dioxide out of the solvent or sorbent, so you can store or reuse it. This process typically requires a lot of energy.

Schematic diagram of Climeworks’ DAC technology Source: Climeworks.

Exactly how much varies a lot depending on the process involved. In any event, this energy use makes DAC expensive relative to alternatives, potentially ranging from USD$50 to $1,000 per tonne of CO2. DAC technologies using amine solvents also use a lot of water. And depending on where you get your energy from, extracting carbon dioxide from your solvent or sorbent could also involve the release of a fair amount of carbon emissions, somewhat negating the point of DAC in the first place.

The Outlook

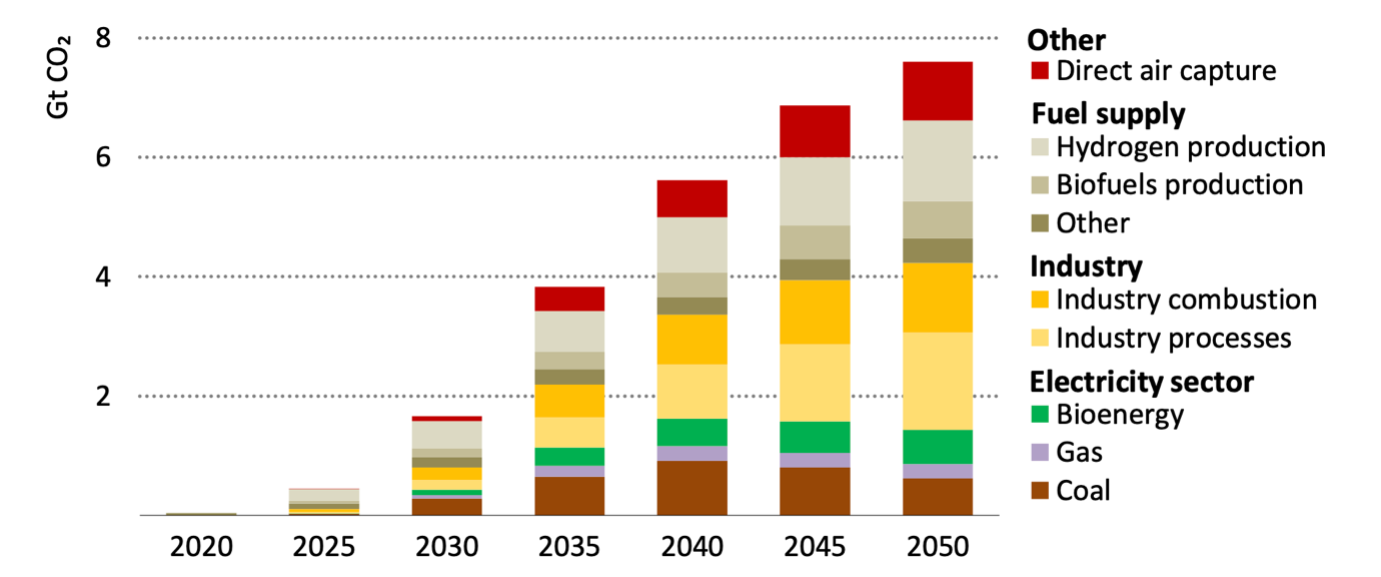

Net-zero pathways see an increasing role for DAC as the timeframe required for carbon reduction narrows. The IEA, for example, expects DAC to be responsible for 13% of global carbon removal by 2050. But a major problem for DAC at present is that the process costs more than what the market is willing to pay for carbon.

Global CO2 capture by source in the IEA’s net zero pathway. Source: IEA Net Zero by 2050 report.

So, unless customers want to pay over the odds for carbon removal—and some corporations may be happy to do so as part of their carbon-offsetting strategies—the large-scale deployment of DAC seems unlikely unless the cost of the process comes down and/or the price of carbon goes up. DAC also competes with cheaper carbon removal technologies, including nature-based solutions such as reforestation and point-source CO2 capture where carbon is captured directly at sources such as power stations and factories.

That hasn’t stopped start-ups from attempting to crack to the market. Among the more notable players is Carbon Engineering of Vancouver, Canada. The company has attracted backing from Bill Gates, Chevron Corporation and Occidental Petroleum, among others. Others to watch include Climeworks, which is involved in an important DAC project in Iceland, and Global Thermostat, which is working with Coca-Cola to supply climate-friendly carbon for carbonated drinks and with Porsche to produce carbon-neutral vehicle fuels.

It remains to be seen whether these companies and their brethren can bring about the establishment of a viable market for DAC. The technology is likely to play some role in a broader carbon management approach to achieving net zero. And for now, DAC has one thing going for it, at least: in the US, it is one of the few climate-related concepts that both Democrats and Republicans could be happy to support.