Welcome to the latest Energy Transition Insight, tracking opportunities in the evolving energy sector.

Our Atlas and New Energies teams recently hosted a webinar titled ‘UK and Norway – The role of exploration in the Energy Transition’, which kicked off with a review of exploration activity and performance in the UK and Norway over the last decade, then provided an outlook for exploration in 2023, and lastly discussed Energy Transition in the North Sea including the UK’s first carbon storage licensing round.

The progress in the Transition is our focus for this issue. As we approach the halfway mark for the year, this insight provides a summary of those themes in the UK and Norway.

Energy Transition themes in the UK and Norway

In recent years, the energy trilemma in the UK and Norway – that is security, affordability and sustainability – has seen significant movement in the latter. Governments set Net Zero targets in law and discussions focused both on phasing out fossil fuels, while also decarbonising the existing oil and gas (O&G) industry. However, an energy crisis accelerated by the war in Ukraine followed by a potential financial crisis, has increased attention on both security and affordability.

As we approach the halfway mark in 2023, it is worth reflecting on how much has changed, and whether the pace of the Transition has slowed or sped up. Westwood has released several insights, reports and white papers, which highlight that despite some rebalancing in all aspects of the energy trilemma, the Transition is continuing at pace. The question now is whether enough is being done, and if the right balance is being struck across all elements of the trilemma.

The below summarises a selection of those key themes with links to previous material in case you missed it.

Emissions performance in oil and gas

Greenhouse gas emissions from offshore O&G production facilities have reduced in recent years.

The UK has achieved a reduction in absolute emissions from offshore O&G assets from 13 million tonnes of CO2 in 2018 to 10 million tonnes of CO2 in 2021. While some assets have improved the emissions performance as companies focused their attention on operational advancements and efficiencies, Westwood analysis concluded the reduction is due, in part, to reduced offshore production and hub closures. The challenge is whether the country can maintain its downward trend while balancing the demand for increased production. To continue decarbonising the offshore industry, UK hubs will need to focus on higher capex solutions, such as electrification.

Norway has a long history of offshore electrification of O&G production and in recent years the increasing number of electrified platforms has maintained the country’s downward trend in absolute emissions. In 2022, there were 6 hubs which were partially or fully electrified, with some of these facilities producing at less than 1 kgCO₂/boe. With firm plans for further electrification, Westwood forecasts that Norway’s performance will continue its downward trend in absolute emissions in future years.

Electrification from offshore wind

The Hywind Tampen offshore wind farm in Norway, which is directly connected to the Snorre and Gullfaks hubs, recently started to partially power O&G field installations at Snorre following first power to the Gullfaks A platform in November 2022 and is due to come fully online shortly. With power from shore proving to be both a challenging and expensive solution in the UK, the country has looked to accelerate the integration of offshore wind with O&G through the introduction of the Innovation and Targeted Oil & Gas (INTOG) round. Introduced in 2022, the goal of INTOG is unique, aiming to encourage further innovation in the offshore wind sector and create an opportunity for offshore wind to decarbonise O&G assets. The TOG part, for projects connected to O&G platforms, follow a ‘Proportionality Principle’ where developers can bid for no more than five times the demand it intends to satisfy to O&G operators for a minimum of five years of demand. The water depths and distances from shore lend themselves best to floating wind.

The INTOG results were announced in March of this year, and of the 5.4 GW of total capacity awarded as part of INTOG, TOG accounted for 4.9 GW split across eight projects. While the process has the potential to support emissions reduction from O&G assets in the UK, only a few platforms will benefit. Assuming a windfarm is operational in 2027 and considering the minimum requirement of five years of demand, hubs set to cease production in that time are unlikely to benefit from INTOG and will need to consider alternative decarbonisation solutions.

Floating offshore wind is not the solution being selected by all and presents both economic and technical challenges. The Trollvind project in Norway, a ~1 GW floating offshore wind farm looking to electrify the Troll and Oseberg facilities through an onshore connection point, was recently placed on hold indefinitely. The project developer, Equinor, stated that due to rising costs, the project can no longer be developed without financial support, making it commercially unviable. Equinor also stated that the preferred technology for the wind farm is not available due to changes in the technical solutions, making the concept less viable.

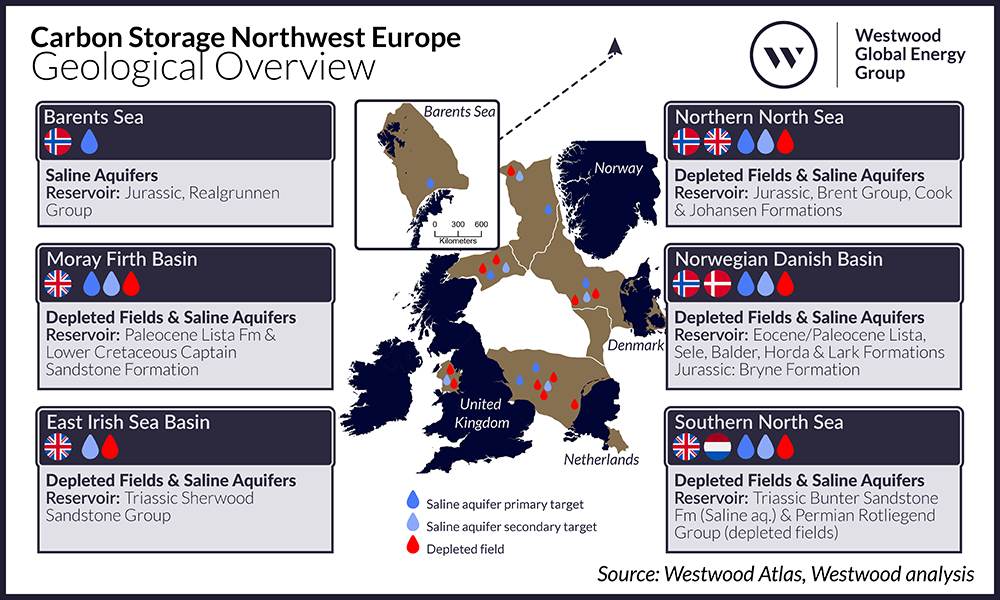

CCS in UK and Norway ramping up

Europe boasts an estimated 500 GT of theoretical capacity for CO₂ storage, with a significant portion of this offshore UK and Norway, in both saline aquifers and depleted hydrocarbon fields. Both countries have significantly increased carbon capture and storage (CCS) activities in recent years with a sharp rise in the award of carbon storage licences. Norway continues to offer acreage out of round while the UK recently announced preliminary results of the UK’s first carbon storage licensing round with the offer of awards for 20 carbon storage licences to 12 companies. The new sites offer significant storage opportunity, storing up to 10% of the UK’s annual emissions. Interest in the Round was high and traditional E&P companies were joined by new entrants to the market. Based on company announcements and Westwood analysis, it is likely that the large E&P companies will be the most successful in the Round, with smaller companies gaining access through partnerships. Westwood recently completed a Full Analytical Report on the Round, which is available to download.

Other significant developments driving the CCS industry in 2023 so far, as touched on in our previous article, include:

Changes in Ownership: This year we have seen numerous changes of ownership in projects, as companies streamline their ET interests. BP recently joined Harbour Energy on the Viking CCS project, Shell and National Grid exited the Northern Endurance Partnership, while Equinor and Vår Energi left the Barents Blue ammonia and associated carbon storage project.

Government Investment: In the UK, the government pledged to invest £20 billion over 20 years to scale-up CCS projects. As part of the Track-1 cluster sequencing process, the first tranche of carbon capture projects was shortlisted from 20 down to eight and there were further announcements on the long-awaited Track-2. An Expression of Interest (EoI) period opened for a month, with Viking CCS and Acorn the likely front runners to be selected, although Morecambe Net Zero Cluster and Solent Cluster both confirmed they submitted an EoI.

European Countries Strengthen Ties: Norway continues to strengthen ET ties with Europe and break down barriers to CO₂ transport. In April, the EU and Norway established its Green Alliance, to strengthen their joint climate commitments and cooperation on the clean ET. Belgium and Norway also recently started formal negotiations for cross-border transport and storage of CO₂.

Different approaches to hydrogen

Attention on hydrogen has increased in Europe due to concerns around energy security. Both the UK and Germany doubled their hydrogen targets from 5 GW to 10 GW and the Netherlands wants to double their current target to 8 GW. The UK and Norway are pursuing both blue and green hydrogen, although the drivers for each is quite different.

With an electricity grid that is almost entirely renewable and over 50% of the national emissions coming from offshore O&G, Norway’s approach to hydrogen has moved beyond national decarbonisation. Their hydrogen strategy is very much focused on exports, be that either as hydrogen, or via heavier energy density carriers such as ammonia, to support European needs.

In the UK, with large industrial heartlands and several heavy industries that will require fuel switching to hydrogen to decarbonise, the focus on hydrogen production is very much for internal use in the short-term then export to Europe in the longer-term. Blue hydrogen projects are forming the backbone of early carbon storage projects while green hydrogen projects are developing in more geographically dispersed areas supporting local consumers. Westwood’s White Paper explores the key factors priming hydrogen for success in the UK market.

It has already been a busy year in Northwest Europe’s Energy Transition. Major project and policy announcements will continue to shape the landscape and Westwood is excited to see what the next six months bring.

Stuart Leitch, New Energies Research Manager

[email protected]