There is something quite seductive about the potential of biofuels in the energy transition. Conceptually, the creation of biofuels, which the European Commission defines as ‘fuels derived directly or indirectly from biomass,’ is akin to a speeded-up version of the decomposition processes that led to oil and gas over millions of years.

Biofuel products such as biodiesel or renewable natural gas (RNG) can in most cases serve as a direct replacement for fossil fuels, allowing oil and gas companies to use their existing infrastructure for storage and transport. At the same time, biofuel production is much less hazardous than drilling for hydrocarbons in remote, harsh locations such as the North Sea or the Arctic Circle. And if the biofuel can be made from organic waste, it can contribute to a more circular economy.

Importantly, too, the similarity between biofuels and fossil fuels means end-use applications can switch from one to the other without the need for major technology shifts. That is one reason (apart from the lack of feasible alternatives) why the aviation industry is keen on biofuels: it could use them without having to change today’s aircraft.

Given all these advantages, it is hardly surprising that oil and gas companies are eyeing biofuels with interest. Shell, for example, is building one of Europe’s biggest biofuels plants, in the Netherlands, and is considering another one in Singapore. BP, meanwhile, has invested in Fulcrum BioEnergy and Green Biofuels, and has a joint venture with Bunge in Brazil. Chevron has also created a joint venture with Bunge. And ExxonMobil is working on biofuel development with Biojet of Norway, Clariant of Switzerland and US-based Synthetic Genomics, among others.

Does this mean biofuels are the future for oil and gas? Not quite. The biofuel industry faces a range of challenges. The most obvious and publicly debated one is that if the feedstock for biofuels comes from land-based plants, then these can either end up competing with food crops or “rampant deforestation, habitats wiped out and worse emissions than if we had used polluting diesel instead,” according to one source.

What about waste-to-energy?

One of the main ways this problem can be avoided is by using feedstocks based on organic wastes, such as municipal rubbish or agricultural residues. Eni has such biorefineries in Italy and is looking to develop a plant in Kenya. TotalEnergies also recently agreed to produce 1.5 TWh of RNG per year from Veolia’s global waste and water treatment facilities by 2025.

The volumes are still very small. Today RNG production stands at around 40TWh, representing about 0.1% of global gas demand. The is partly because waste-to-energy is fiddly to get right, requiring the right feedstock sourcing strategy and great care with feedstock recipes for optimum efficiency. The market is also highly fragmented.

And in almost all jurisdictions, and especially in major markets such as California or Germany, the viability of biofuel operations is closely tied to regulation and support schemes, either in the form of quota systems or feed-in tariffs. But these are in flux as each country’s climate strategy evolves. Last year, for instance, German lawmakers unveiled plans to ban palm oil mill effluent as a feedstock. The move is good news for biodiversity in areas being logged for palm oil production—but illustrates the changing nature of waste-to-energy’s regulatory environment. A stable regulatory regime is often cited as key to attracting investment.

Beyond waste-to-energy, recent years have seen significant interest in producing biofuels from algae, an approach that avoids land-use problems and is in theory highly scalable. But to judge from the massive failure rate of venture capital-backed startups in this field, algal biofuels, too, are a concept that is fraught with difficulty. Given these pitfalls, it is perhaps understandable that biofuel production has failed to live up to expectations.

Series 3 of the ‘Energy Transition Now‘ podcast has started beginning with “What Antarctica tells us about climate change”, visit our podcast page.

Better investment opportunities?

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), investment in biofuels and biogases in 2021 is estimated to represent only 2% of all fuel supply investments excluding electricity. At best, the fuels could represent 11% of fuel investment under the IEA’s Net Zero scenario. The IEA’s tracking reports on biofuels conclude that policy actions under discussion “could accelerate demand for sustainable biofuels in the decade ahead.” However, as things stand biofuels for transport are “not on track”—with high commodity prices a near-term obstacle—while bioenergy power generation has been downgraded from “on track” to “more effort needed”.

It remains uncertain how far this picture will change in future. In addition to the challenges outlined above, a further problem for biofuels is that many potentially large industrial end users have wavered over fully committing to biofuel-based decarbonisation pathways. This is the case of aviation, for example, which could be a prime source of biofuel demand but which is also considering a jump to hydrogen engines instead.

In addition, while biofuels are the closest low-carbon versions of fossil fuels that you could hope for, producing them—a process that involves nurturing microbes, algae and similar biological agents—is complex and, so far, has not shown an ability to scale well. The lack of obvious industrial-scale demand and problems in scaling up supply add up to a complex outlook for biofuel investors.

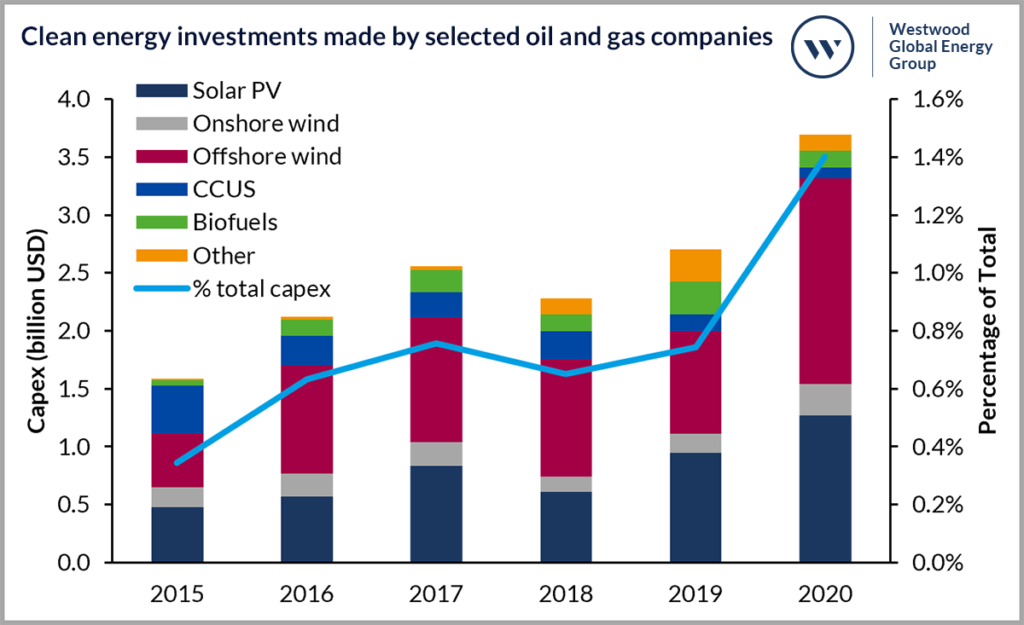

Because of this, it is unsurprising that the oil and gas sector has yet to embrace biofuel production wholesale. Indeed, IEA figures up to 2020 show oil and gas investment in biofuels was being reduced to a fraction of the amounts being spent on solar and wind energy. The situation with biofuels contrasts with that of offshore wind, which is already scaling and lends itself well to the marine, engineering and financial capabilities of oil and gas companies.

Figure 1: Clean energy investments made by selected oil and gas companies

Source: IEA

And mature generation technologies such as wind and solar are now seen as a clear route to creating clean hydrogen, which can then be used as a feedstock for industrial-scale production of synthetic fuels via power-to-X technology. All this is not to say that biofuels will not have a place in tomorrow’s low-carbon energy systems. They almost certainly will, but the question is how significant this presence will be… and the extent to which the oil and gas sector will be involved.

The digest: this month’s key headlines

- Crown Estate Scotland has unveiled details of its Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas offshore wind leasing process, which is open to innovative projects under 100 MW plus plants that will help cut the emissions of fossil fuel extraction operations.

- Public disaffection with fossil fuel companies in the UK was underscored when the UK’s National Portrait Gallery severed its 30-year partnership with BP. The Tate and The Royal Shakespeare company have also cut ties with the oil major.

- Researchers have called out BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Shell for failing to match energy transition claims with actions. “Accusations of greenwashing appear well-founded,” they conclude.

- The US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has issued policy statements to tighten controls on new gas pipelines and stop unnecessary ones from going ahead.

- France appears to be doubling down on nuclear in a bid to cut energy sector emissions, with President Emmanuel Macron announcing plans for at least six new reactors.

- The International Energy Agency’s Global Methane Tracker reveals methane emissions from the energy sector are 70% higher than official figures.

- Wind turbine giant Siemens Gamesa has replaced its chief executive following repeated profit warnings.