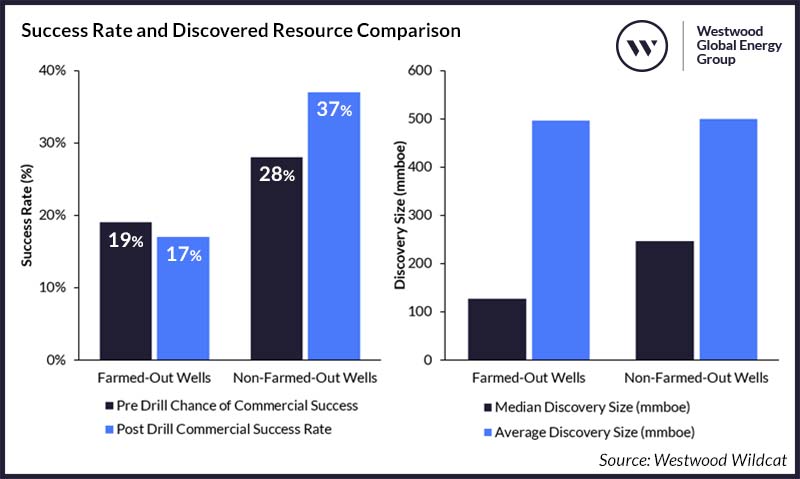

Since 2017 high impact (HI) exploration wells drilled outside USA and Canada, where equity was farmed-out by one or more of the participants before drilling, had approximately half the commercial success rate and median discovery size than those wells that were not farmed-out.

In a recent farm-out drilling performance study, Westwood analysed the results of 419 high impact exploration wells drilled outside the US and Canada, which completed between 2017 and end October 2022. 26% of these wells had been subject to a farm-out deal and a proportion of the cost of the well was covered by the company farming-in.

The analysis shows that companies usually know which are their best prospects and have reduced their exposure to exploration failure by selling down their equity in lower ranked prospects before drilling, whilst those who choose to farm-in have exposed themselves to lower success rates and smaller discoveries.

Success Rate and Discovered Resource Comparison

Source: Westwood Wildcat

Exploration for hydrocarbons is a high-risk business and only one in every three high impact exploration wells drilled between 2017 and end 2022 resulted in a potentially commercial discovery. The cost of failure can be high and explorers will try to manage their exposure according to their appetite for risk. Exploration companies frequently invite other companies to join them in the venture in order to share the cost and the risk, by farming-out equity in planned wells.

Companies have been farming-out higher risk wells

Westwood assigns a pre-drill chance of commercial success to exploration wells based on the historical success rates of analogue prospects. The average pre-drill estimated chance of commercial success for wells that were farmed-out was 19% compared to 28% for wells which were not farmed-out. Companies tend to sell equity in higher risk wells.

Farm-out wells have a lower commercial success rate

The actual commercial success rate of high impact exploration wells that had been farmed-out and were completed between 2017 and end October 2022 was 17% compared to a commercial success rate of 37% for those wells that had not been farmed-out. The success rate of farm-out wells was slightly less than would have expected for, whilst wells that were not farmed-out had a significantly higher success rate than historical analogues. Companies tended not to farm-out prospects that they knew to be lower risk.

Farming-in can be successful but may result in smaller discoveries

The difference in success rates should not be taken as an argument against ever farming-in. For some companies, a decision to farm-in to an exploration opportunity can pay off handsomely. Between 2017 and end October 2022, 19 commercial discoveries were made from the 111 farmed-out wells, discovering an estimated total of 10 billion boe of oil and gas. This compares to an estimated 60 billion boe of oil and gas resources discoveries by non-farmed-out HI wells. The average size of discoveries made in wells that had been farmed-out is very similar to that of those that had not, at ~500 mmboe. This is, however, biased by a few giant discoveries such as Venus in Namibia (3 bnboe), Yakaar in Senegal (2.5 bnboe) and Ken Bau in Vietnam (1.25 bnboe). The median size of discoveries made in farmed-out wells is just 127 mmboe compared to 246 mmboe in discoveries that had not been farmed-out. Farm-out discoveries are generally smaller.

Exploration companies have been successfully reducing their exposure to failure by farming-out their equity in high impact exploration wells with a lower chance of commercial success and smaller volumes than those where they retained their equity from the time when they entered the licence.

Farming-in to drilling opportunities can bring great rewards. Just look at Hess and CNOOC’s successful farm-in to the Stabroek license in Guyana in 2014, accessing 55% of nearly 11 billion barrels. Nonetheless, the statistics show companies choosing to farm-in should be mindful of the concept of “caveat emptor” or “let the buyer beware”.

Christine Shearman, Senior Analyst

[email protected]